Do We Need to Train to Failure?

Study review looking at hypertrophy and strength outcomes from failure vs non failure training in high load and low load groups.

Spark Notes

You don’t need to train to failure in order to maximize hypertrophy (muscle building) as long as you’re training with heavy loads (80% of 1RM is often used in the literature).

If training with light loads (30% of 1RM often used), then it does seem like you’ll need to train to failure in order to make similar gains in muscle as you would training with high loads, but not to failure.

For strength outcomes, even training with light loads to failure didn’t result in similar strength outcomes as when training with heavy loads not to failure.

There was no difference in strength or hypertrophy outcomes between high load groups when training to or not to failure as long as total volume was similar.

Training with high loads not to failure may be favourable as to make similar gains without accumulating as much fatigue.

With that being said, you should train to failure at some point so that you can more accurately gauge what failure actually feels and looks like to you.

The training to failure debate is an old and highly contentious one. And I get it. Old school lifters understandably may feelslighted by the up and coming lifters who claim to be able to make similar gains, without actually having to grind out those gruelling “Jesus take the wheel” sets to true failure.

One may argue that it’s a Meathead’s rite of passage to have endured their share of life threatening sets, and to have come through on the other side with some sick gains and a battle tested resume in the gym.

The issue is, plenty of research over the last while may be pointing to the fact that this rite of passage may sadly, not be evidence based.

Personally, when I take my science hat off and rock my grungy, iron tested, meathead cap, I tend to agree with the old school folks. As I think a lot of people read “you don’t need to train to failure” as a pass to utilize easy sets in the gym.

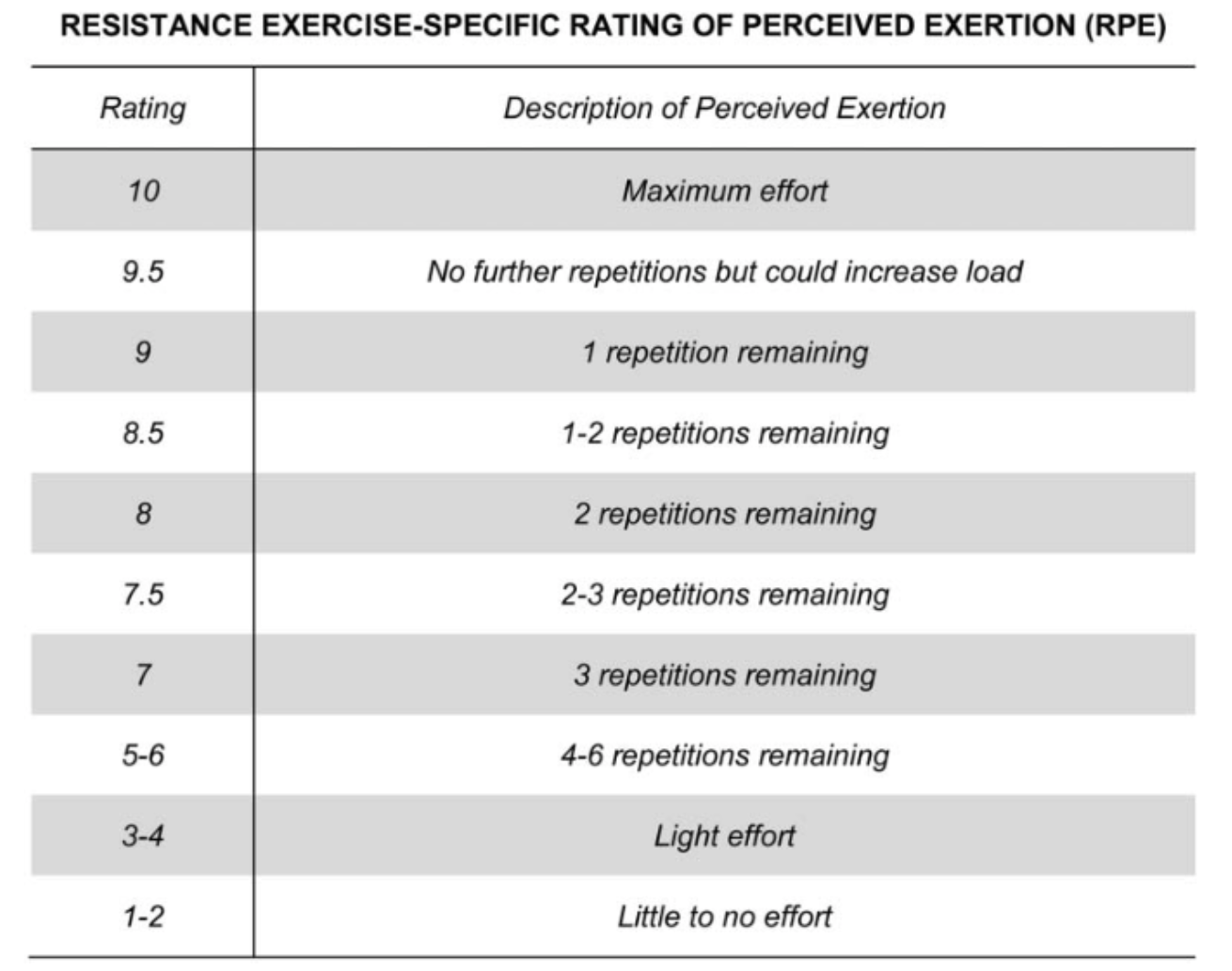

We need to able to understand what training to failure actually looks and feels like in order to properly gauge the intensity of our non failure training. Commonly RPE or RIR is used here.

RPE= rate of perceived exertion

RIR= reps in reserve

Here you’ll see a model from Dr. Mike Zourdos to depict what the RPE scale looks like. The flaw with never having trained at or really close to failure, is that you may think you’re at 9, but you’re actually at 5 or 6.

In this case, you’d be leaving a lot of reps in the tank and perhaps may be training too far from failure, to really maximize your gains or even worse, too far to make any noticeable gains at all.

This is where the old school folks have a solid ground for their arguments. I’d speculate their RPE barometers are more accurate than someone who’s never trained to failure.

Even I’m still trying to get better at gauging my RPEs. I like to use rep out sets as a strategy to do so. Below you’ll see an example. The weight I was using for my working sets of 6 reps, was 325lbs. For my last set, I decided to rep out as many as I could without too much technique breakdown. I ended up getting 12 and to be honest, I probably could have done 2–3 more. This left the prescribed set of 6 to be at an RPE of around 4–6. Which I believe would be leaving too much in the tank If I’m trying to maximize my strength & hypertrophy gains.

This doesn’t make these sets useless either. It just makes them less stimulative than I had thought, which is totally okay. I actually used this as feedback to increase my loads for the following week.

What does the previous evidence say?

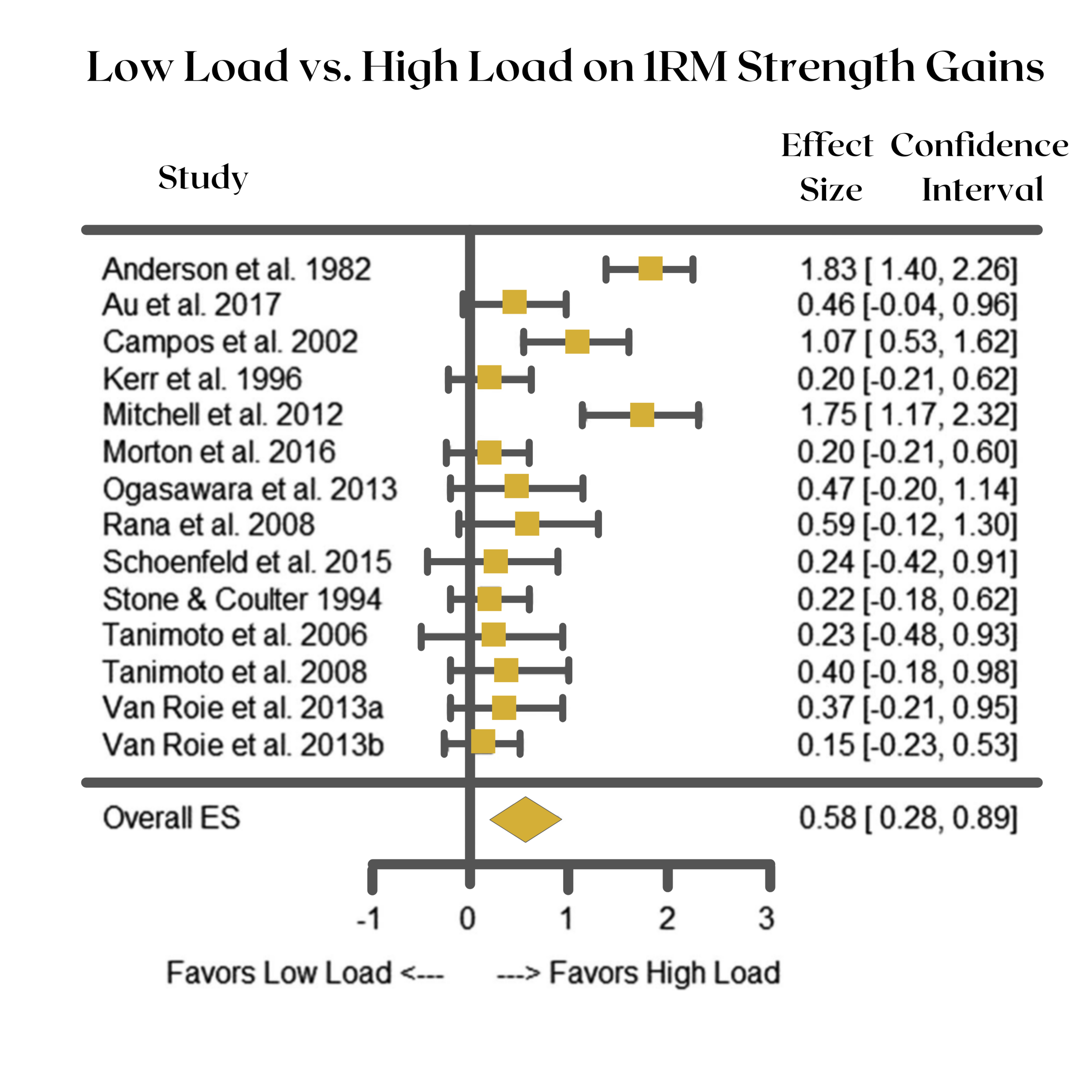

When it comes to looking at the evidence, let’s take a very brief look at a meta-analysis from Brad Schoenfeld and colleagues from 2017.

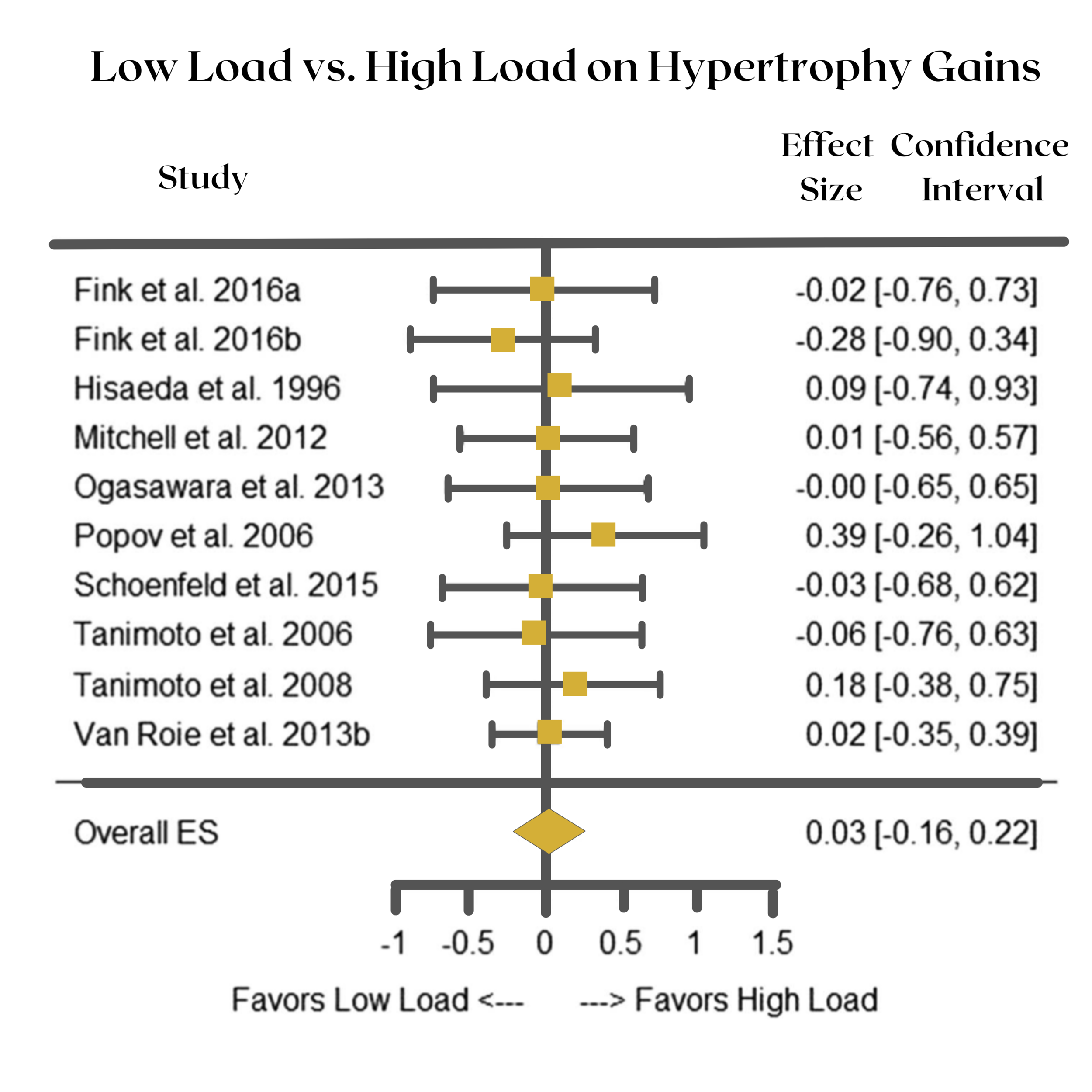

This paper meta-analyzed 14 studies on the effects of high load vs low load training to momentary muscular failure for strength outcomes, as well as 8 studies for hypertrophy outcomes.

Adapted from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

When looking at strength outcomes, high load groups had a statistically significant and “medium” effect size favouring their outcomes over the low load group. Even though all studies trained to what was termed momentary muscular failure.

adapted from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

When looking at hypertrophy, the outcome virtually straddled the “null”, meaning there was no difference between low load and high load training in terms of gaining more muscle, as long as they were training to failure. In fact, most of these studies didn't even equate volume, which is a downside of this meta.

All in all, this is a decent framework to start from. In short, it looked like when trying to maximize strength, we should train with heavier loads as even training to failure with lighter loads won’t yield the same gains in 1 rep max strength, as when training with heavier loads (pretty intuitive).

Conversely, as long as you’re training to failure according to the results above, high load or low load doesn’t seem to have a clear winner.

This brings us to study at hand.

This study experimented with 4 groups over an 8 week training program. The program used single leg knee extensions to see if there was differences between strength and hypertrophy outcomes between them, in volume equated programs. All groups did two sessions per week for a total of 16 sessions.

The groups were:

High load to failure (HL-RF)

High load not to failure (HL-RNF)

Low load to failure (LL-RF)

Low load not to failure (LL-RNF)

The sample group was on 25 untrained men, with an average age of about 23 years old.

The subjects were randomized to the high load or low load group and their limbs were randomized to either the failure or non failure group. This may sound strange, but I’ll simplify — if you were randomized to the high load group, one leg did knee extensions to failure and the other not to failure.

1 rep max tests were done before and after the study, as well as quadriceps cross sectional area was measured via MRI to assess hypertrophy.

Each session started off by training the “failure limb” for three sets to failure. Then 60% of the average repetitions per set, was taken and applied to the non failure limb. Since volume was equated, the non failure group had to do more sets of course since they were doing less reps per set.

Low load training was at 30% of 1 rep max and high load training was at 80% of 1 rep max.

Here was the average set and rep outcome per group below:

High load to failure — 3 sets of 12.4 reps

High load no to failure — 5.5 sets of 6.7 reps

Low load to failure — 3 sets of 34.4 reps

Low load no to failure — 5.4 sets of 19.4 reps

The last thing worth mentioning was that RPE was reported by each subject 30 minutes after every session to gauge how challenging on a scale of 1-10 that session was for either limb.

Results

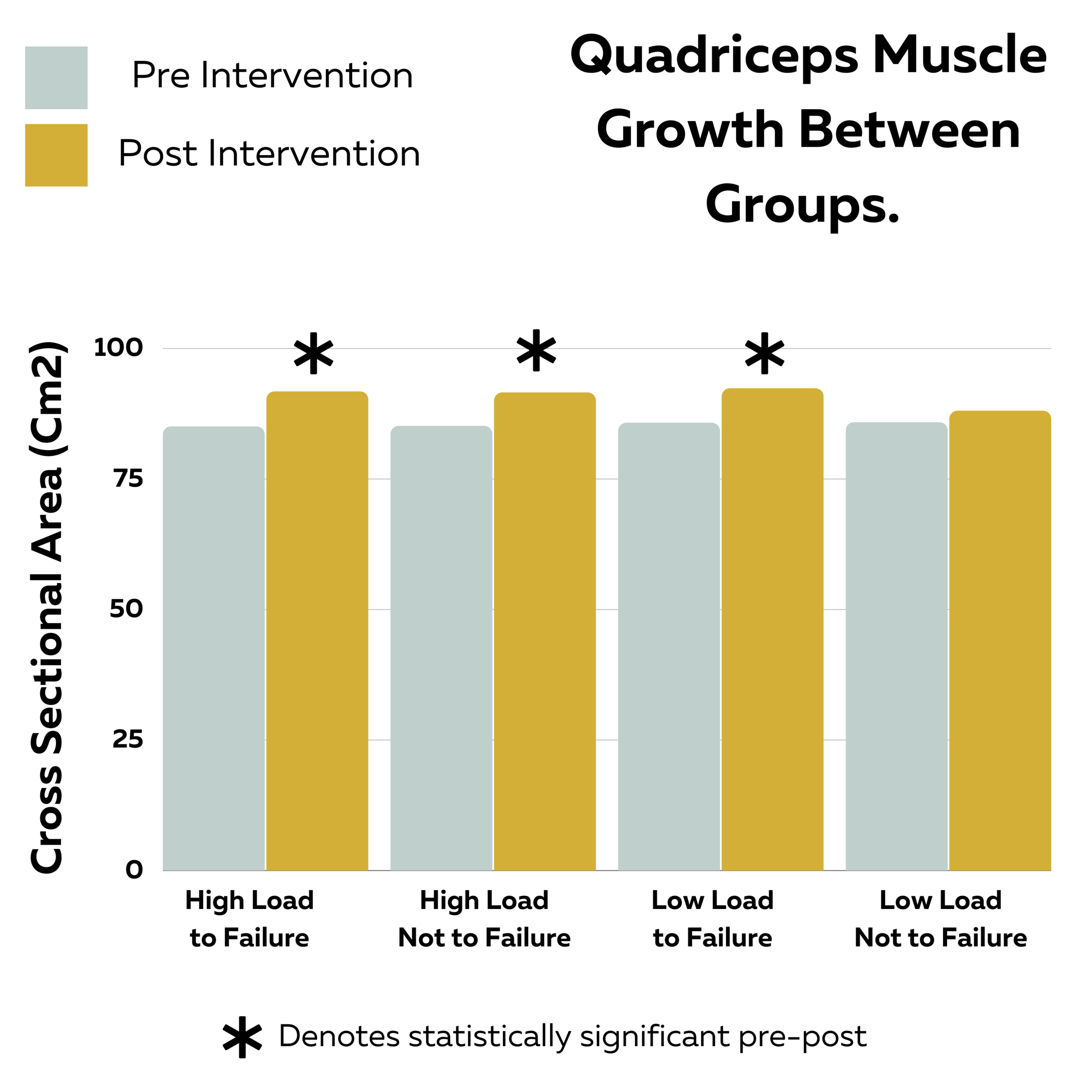

In terms of hypertrophy outcomes, the HL-RF, HL-RNF and LL-RF all saw significant increases in hypertrophy. The LL-RNF group saw no significant increases in quadriceps hypertrophy.

There was no statistically significant differences between the three groups that did see gains in muscle, but the effect sizes did slightly favour the high load groups, even though it was not statistically significant or even practically meaningful.

Effect sizes for hypertrophy among groups:

High load to failure effect size = 0.57

High load not to failure effect size = 0.60

Low load to failure effect size = 0.45

Load load not to failure effect size = 0.15

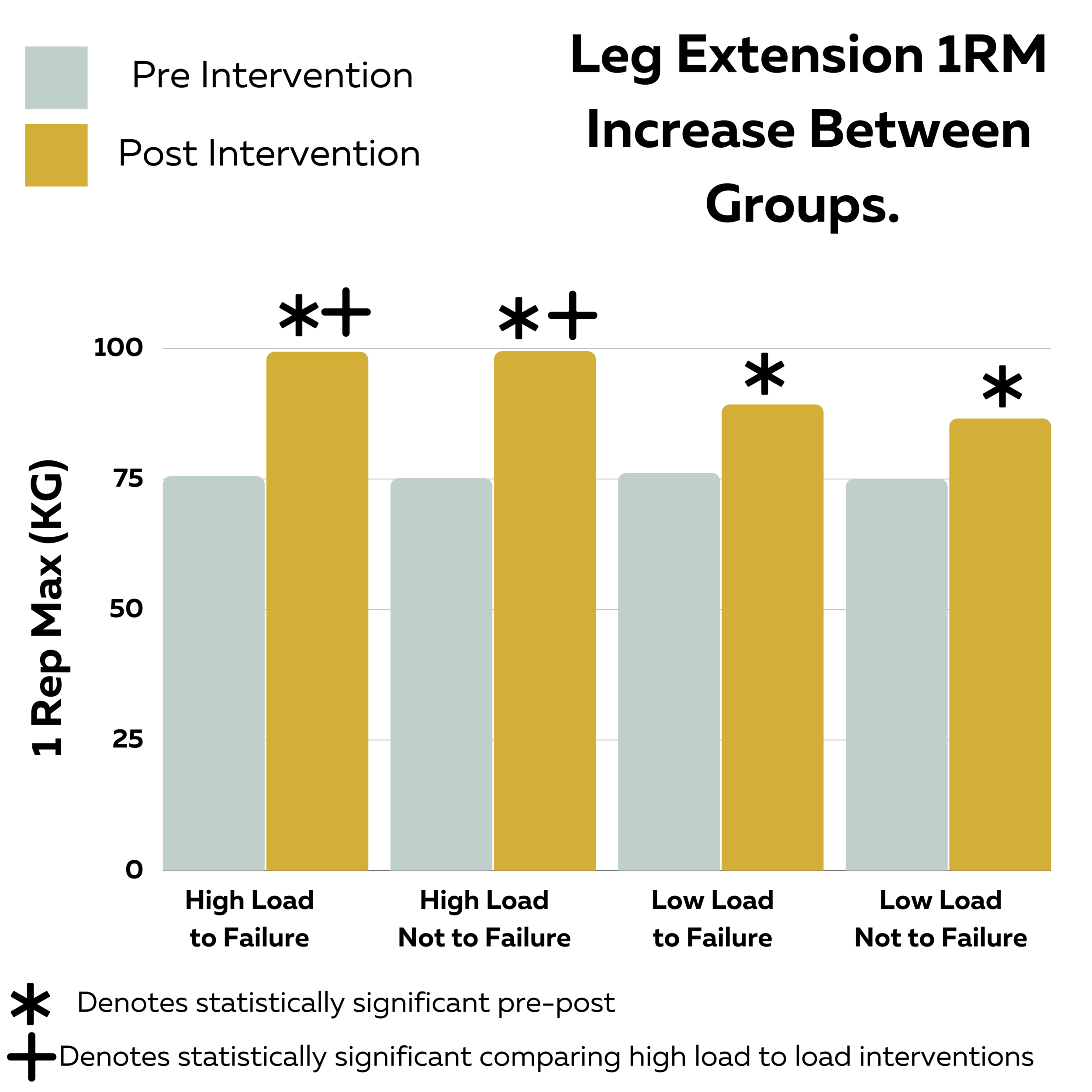

For strength outcomes, all groups saw statistically significant increases in 1RM strength compared to baseline. With that being said, both high load groups saw significantly more gains in strength than both low load groups, regardless of training to failure.

Interestingly here, even when training to failure, the low load group saw the same gains in strength as the non failure low load group. Which really speaks to the specificity of strength. This also is in line with the previous meta-analysis which showed high load training to be superior than low load training (even when training to failure) for maximizing strength.

Here are the effect sizes for 1RM strength gains below:

High load to failure effect size = 1.24

High load not to failure effect size = 1.25

Low load to failure effect size = 0.82

Load load not to failure effect size = 0.89

Brief understanding of effect sizes: An effect size of “1” means that the mean for that group moved over 1 standard deviation after the intervention. For the 0.82 effect size above, this means the average strength for LL-RF increased by 0.82 standard deviations after the 8 week trial. While the HL-RF group mean strength increased by 1.24 standard deviations after the 8 week trial.

Lastly, when it came to reported RPE, both reps to failure groups (high load and low load) reported significantly higher RPEs than the non failure groups.

You can see that both HL-RF and LL-RF consistently were in the 9–10 RPE range. While the HL-RNF group flirted between 6–7 for most sessions. Which is useful to see since they actually made similar gains in strength and hypertrophy as the the HL-RF group and better gains than the LL-RF group. Even though the sessions were perceived to be easier.

Applications

Applying these findings can get murky. As yes, this does show perhaps the best bang for your buck for strength and hypertrophy, is when training at high loads but shy of failure. With the obvious caveat that you’d do equal volume than if you were training to failure.

Heres the murk, the sets in this study that weren't taken to failure, might still have been harder sets than you do on average. I can admit they’re probably harder than a lot of mine.

I think it goes underestimated how hard people train in exercise science studies. It’s not exactly comparable to training alone after work, when you’re tired, tinkering around your phone and taking your time.

In an exercise science lab, you’re there to train. And if you’re competitive at all, you’re probably pushing yourself harder than you ever have while alone at the gym.

In fact, one study took 160 trained men, asked them “how much do you usually bench for 10 reps?” and then tested it in a study. They banged out 16 reps on average in the study with a load they said they usually do for 10. This was also in trained folks too.

My point is, once again, if you’ve not trained really hard for a period of time and have never actually trained to failure, this framework isn’t one to get too attached to.

As what you think training away from failure looks like might actually be so far from failure that you’re leaving a lot of gains on the table.

But if you’ve had your fair share of “hold my beer, I’m about to do something wild” sets, this is valuable information to have. As taking every set or even most sets to “gun to your head failure” really doesn’t seem to be necessary.

In fact, training with heavy loads, just shy of failure could yield similar gains with lower session RPEs. Over a full week of your training, this could be clutch. This study was on untrained folks, but similar strength and hypertrophy gains have been seen in trained folks when comparing failure to non failure training.

With this framework, I would still utilize failure and “rep out” sets in your training. I just wouldn’t rely on them for the bulk of your training. I personally use rep out sets for a lot of my last sets of the given exercise I’m doing — especially for my lesser fatiguing exercises i.e. not squats and deadlifts. If I can bang out 2–3 more reps than prescribed on my last set, I use it as feedback to increase load for the following week.

For less trained folks, I would recommend this or a strategy similar to this for sure. As a key skill I suggest honing in on, is continuing to get better and better at gauging RPE, or simply how many reps you have in the tank after each set. This way you have a better idea of how hard you’re actually training.

In summary, you don’t need to train to failure to maximize strength and hypertrophy gains. In fact training with heavy loads (around 80% 1RM) just shy of failure (anywhere between 1–5 reps depending on who you ask) has been shown to yield similar gains as when training to failure with the same heavy loads, as long as you’re doing equal or at least similar volumes. The benefit could be similar gains with less accumulative fatigue. As mentioned above, this is all under the caveat that you have trained to or damn near failure enough to accurately estimate how close you actually are to failure. This makes spending time training really hard and getting better and better at gauging RPE, a crucial component to taking that next step in the gym.

Happy lifting. 🤘🏽

Coach Dylan🍻

References:

Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26049792/

2. Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations Between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28834797/

3. Muscle Failure Promotes Greater Muscle Hypertrophy in Low-Load but Not in High-Load Resistance Training

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31895290/

4. Self-Selected Resistance Exercise Load: Implications for Research and Prescription

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29112055/

5. Effect of resistance training to muscle failure vs non-failure on strength, hypertrophy and muscle architecture in trained individuals

https://www.termedia.pl/Effect-of-resistance-training-to-muscle-failure-vs-non-failure-on-strength-hypertrophy-and-muscle-architecture-in-trained-individuals,78,40974,1,1.html