You Should Probably Be Taking Creatine

What the evidence says and what it also can teach us about the supplement industry.

Spark Notes:

Creatine is the one of the most researched and effective supplement in the fitness industry. When compared to placebo, creatine supplementation consistently increases strength performance and gains in lean body mass.

These effects are most profound in shorter, more intense performance tasks.

The magnitude of positive benefits tends to be the “small” effect size range.

2–5 grams per day of creatine monohydrate per day will be sufficient for most folks

Understanding how much research it takes to understand the effectiveness of any one supplement can really help protect you from falling into the hype that is so pervasive within the fitness/nutrition supplement industry.

When it comes to supplements, you may be surprised at who I believe is king. It’s not caffeine. It’s not beta alanine. Lastly, it’s not even creatine.

The real king of supplements is hype, marketing and novelty. I say this because, if you look at the evidence for supplements within fitness, creatine is and has been the most effective supplement out there. Yet, it’s clout is still pretty weak when you consider how much more effective it is than a lot of the unproven, newer supplements that are always coming out of the pipeline. This is because it lacks hype, isn’t overly marketed and isn’t new. Some unfounded myths are still pervasive around it, which also doesn’t help.

So let’s talk about creatine. What it is, how it works, what the research shows and lastly, how you can start taking it.

What Is Creatine?

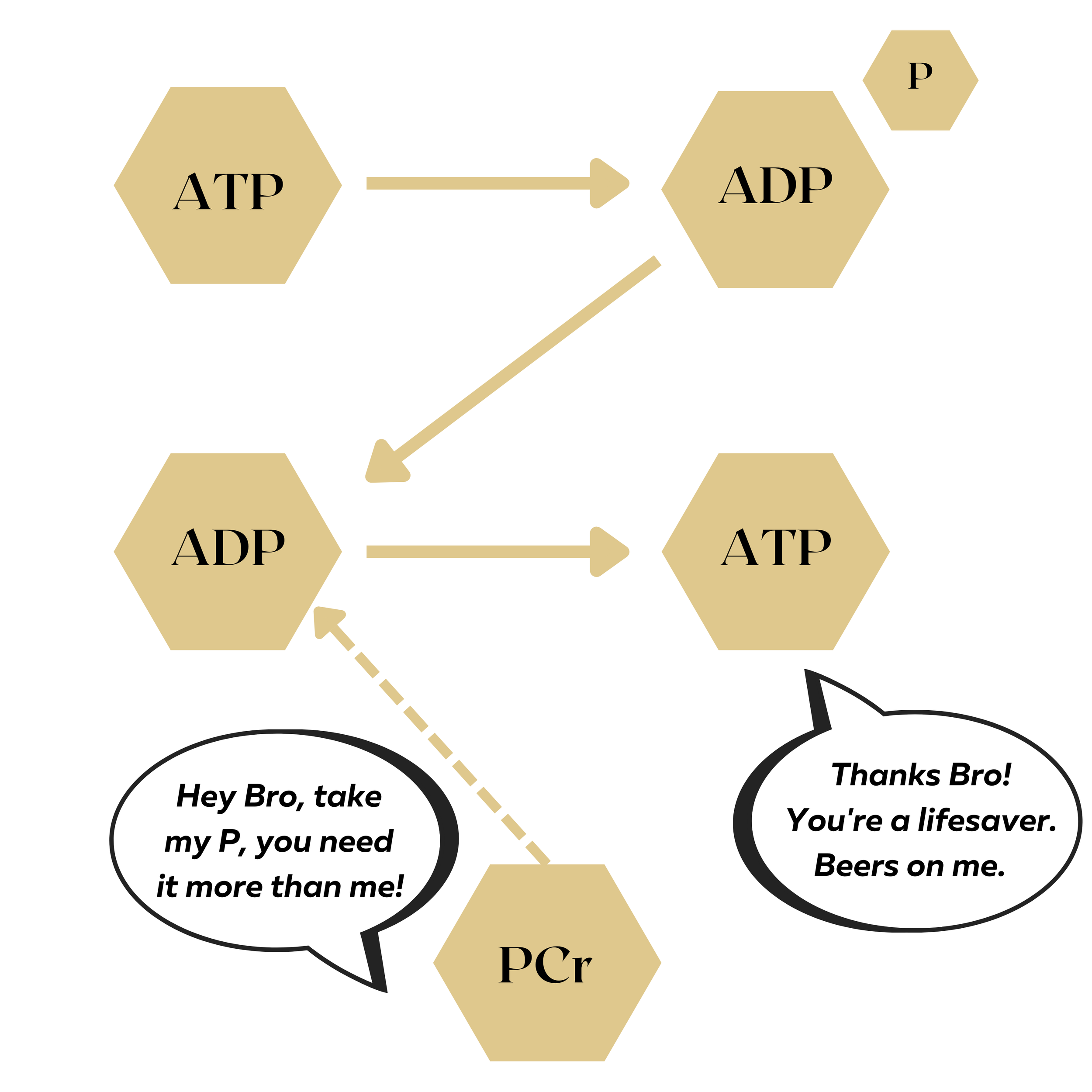

Simply out, creatine is a tripeptide which is a molecule made of three amino acids. Creatine helps form phosphocreatine (in your muscles in this context), which serves as a reserve for those high energy phosphates.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is kind of like the energy currency of the cell. When cells use ATP for energy, the ATP turns into ADP (only having two phosphates now). Phosphocreatine can then donate a phosphate to that ADP to regenerate ATP in a rapid manner.

This is especially useful for high intensity exercise (sprinting, lifting heavy etc.) since that ATP can be rapidly regenerated in this case. Your mitochondria (the powerhouse of the cell, as we all know from grade 9 biology) will also be working away to generate ATP, but just can’t regenerate it at the rapid pace that this immediate donation can do so. Hence why creatine is more helpful during high demanding, intense exercise.

Why Take Creatine?

With what I just talked about in mind, creatine supplementation can help fully saturate your muscle cells with PCr. You will likely consume some creatine in your diet, but not enough to fully saturate your cells. So creatine supplementation is the best option for this.

What Benefits Will I Get From It?

Given it’s ability to increase the saturation of PCr in your muscles, consistent strength gains have been observed from supplementation. Along with some slight increase in lean body mass. The biggest meta-analysis to date on placebo controlled trials (unfortunately all the way back from 2003), showed generally positive outcomes from creatine supplementation across a wide spectrum of metrics and performance related tasks, but most pronounced in short tasks (equal or less than 30 seconds.) This paper also observed a small impact on gains in lean body mass.

In relation to the topics most of my readers are interested in, creatine supplementation led to positive outcomes for both 1RM strength and lean body mass. Both being what would be considered “small” effect sizes (0.33 for LBM & 0.32 for 1RM.)

There was a more recent study from 2017 that showed the creatine groups to elicit significant gains in muscle mass in the upper and lower limb muscles. While the placebo group made some gains, but not a statistically significant amount. The creatine group also made significantly more upper limb gains than the placebo group.

This cohort was also on young men with some resistance training experience, having averaged around 17 months of prior training.

In terms of both of those studies above giving edge to creatine for gains in lean body mass, some of that is likely due to increased water retention in muscle since creatine is considered to be osmolytic and increase intracelluar hydration. This is also nothing to worry about — having a little more water in your muscles, if anything will make them look more full. Which is generally positive thing aesthetically.

Lastly, there were two meta-analysis (where you pool all the data of relevant studies that meet a certain inclusion criteria), one being on lower limb strength, and one being on upper limb strength that showed similar outcomes. There was 60 studies in the lower limb meta & 53 in the upper limb meta. Female subjects were around 25% for both and the age ranges were around 18–70 years old for both. So there was some diversity among participants.

Whether they were looking at total weight lifted or maximal weight lifted, all results were statistically significant in favour of creatine over placebo controls and their effect sizes were all “small” once again.

0.336 positive effect size for max weight lifted in the squat

0.297 positive effect size for total weight lifted in the leg press

0.24 positive effect size for max weight lifted in upper body (bench or chest press)

0.25 positive effect size for number of repetitions done in upper body (bench of chest press)

Summary & Application

The evidence is overwhelming in favour of creatine being an effective supplement for increasing exercise performance and muscle mass. With the effect being most profound in terms of performance increases in shorter, high intensity tasks (usually equal to or less than 30 seconds.) According to the meta by Branch et al. there was still some improvements from creatine supplementation in tasks above 30 seconds and up to 150 seconds — just not as much of an effect as the 30 seconds or less tasks. Lastly, some even milder benefits were seen in the tasks above 150 seconds, but just to the smallest degree when compared to shorter, more intense performance tasks.

Strength, in terms of more traditional gym exercises also consistently showed statistically significant improvements in terms of maximal strength and strength performance. With the magnitude of those increases being consistently in the “small” effect size range.

Gains in lean body mass also seem to be consistent in terms of creatine supplementation when compared to placebo. Part of this is likely water, while part is likely gains in actual muscle tissue.

In terms of using creatine, I think it’s important to keep it simple. While “loading” will get your muscles fully saturated with creatine quicker, you surely don’t have to do this. I generally suggest not doing it either as it can be a burden to pound 20g of creatine a day in the short term and some folks report some stomach discomfort during this strategy. Instead rocking a standard dose of 2–5 grams per day indefinitely should cover your bases. If you’re smaller with less lean body mass, you can hang lower on the scale, and opposite can be said if you’re more jacked. Most scoops will be around 5 grams in the creatine you buy, so this makes it pretty easy to follow these guidelines.

In terms of which type of creatine you should buy, creatine monohydrate is the way to go. Reflecting on how I started this article, you may recall I dubbed “hype” as the real king of supplements. This is an example of this. Considering how widely researched creatine is, the hype is gone. Even though it’s probably the best supplement we have out in the market, it’s just not that exciting anymore. One strategy companies have used is to produce and market new and better forms of creatine — sometimes saying they “don’t cause water retention”. Which if true, would mean they don’t work. These “better” forms of creatine seem to just be novel strategies to charge and therefor make more money from selling creatine. In reality, no alternative forms of creatine have been shown to outperform creatine monohydrate, but they tend to be more expensive.

So creatine monohydrate is the most researched, at least tied for more effective and also the most cost effective. Making it the clear choice.

Final Takeaway: Be Skeptical of Supplements

This last point I’ll keep brief, but I think it’s crucial to hammer home. This entire article was all about one supplement. The most researched and seemingly most effective (legal) supplement in terms of gaining strength and muscle.

Yet, the beneficial effect when compared to placebo was consistently significant, but “small” in terms of effect size. Now, I’ll take those small increases every day. I mean gaining 5% in 1RM strength (referencing Branch et al. 2003) from taking a scoop of a cheap supplement daily is awesome. But this is about as good as it gets in terms of the impact one supplement can make when compared to a placebo. Supplements are just not going to be life changing when it comes to getting strong, lean or muscular.

Most supplements don’t have nearly the research behind them to back the wild claims that influencers, coaches and some Doctors make. The newer the supplement, the less research there usually is on that supplement as well. If we look at creatine in this context, some of the papers I mention here go back nearly 30 years. The meta-analyis from Branch had 100 studies in it — with most being double blind, placebo controlled trials. The newest supplement on the market might have a handful, less, or some cases, zero.

Strangely, in my experience at least, this leads to a phenomenon that I call “the hype/evidence scale.” I’m sure someone else has thought of this before, so I take no credit in being some sort of innovative thinker here. Also, this is not based on science. This is a graph that I made up from my own experience. But, in my experience, the more hype you hear about some supplement, the worse the evidence seems to be. You’ll hear about a new supplement that should be game changing, only to find out theres only one quality study on it with a small sample size. Or even worse, it’s only on rodents.

Then as evidence piles, hype dies down. Even if the evidence is solid. Creatine is a great example here. Yes, most evidence based fitness professionals almost always recommend creatine in the context of strength and hypertrophy, but that space isn’t where hype tends to be as common. The quackery space around fitness and nutrition is where this phenomenon flourishes. Some of those folks will eye roll at something like creatine and hype up some obscure supplement with minimal to no evidence to back it. Ironically, these supplements tend to be stupidly expensive, while much more effective supplements (such as creatine) are dirt cheap in comparison.

A scale that I totally made up just to be a shithead, but holds true in my experience. The more hype a new supplement is getting, especially on social media, should be examined with some serious skepticism first.

So this is me reminding you to be very skeptical in terms of supplements. They live and breed off hype more than they do from high quality evidence. I personally know how badly you may want one supplement to be the cure, but they just don’t exist. At least not they kind they sell at GNC.

There still are supplements that are helpful, creatine being one of them. It’s just an area that I suggest you strongly navigate with skepticism. Wait for strong, real evidence to convince you. Not the charisma of a snake oil dealer telling you everything you want to hear. More often then not, they just want your money. They couldn’t give less of a shit about helping you.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12945830/

2. Creatine supplementation elicits greater muscle hypertrophy in upper than lower limbs and trunk in resistance-trained men

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29214923/

3. Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25946994/

4. Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27328852/

5. Muscle creatine loading in men

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8828669/

6. Efficacy of Alternative Forms of Creatine Supplementation on Improving Performance and Body Composition in Healthy Subjects

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/9000/Efficacy_of_Alternative_Forms_of_Creatine.94079.aspx