What Would Happen if You Overate by 1000 Calories Per Day?

Well… it may depend on your genetics.

Imagine eating 1000 calories more than your caloric maintenance every day.

If you’ve been exposing yourself to overly restrictive eating for a long time, this may sound like a blast.

As someone who’s been on both ends of the spectrum, let me tell you that over eating repeatedly is perhaps just as uncomfortable as underrating repeatedly.

This may sound laughable but imagine drastically over eating on a friday night. Pizza, beers, wings, charcuterie, wine, it doesn’t matter. Whatever floats your boat.

This sounds awesome after a week of none of this. But imagine doing this every god damn day. Passed the point of fullness of 100 days.

Probably at about day 3 or 4 you may start to get really tired of it. This would be like overeating all weekend(fri/sat/sun), but then continuing that behaviour on the Monday.

We often feel really shitty on that Monday and our appetite is quite low. So in this case, in that state, you have to overdo it by 1000 calories again. You can probably imagine this starts to suck real quickly.

Well I bring this up, because a very cool study from back in the day (1990) actually experimented with this.

They overfed subjects by 1000 calories for 84 days out of a 100 day period. Essentially, once a week they didn’t over eat and ate at their baseline caloric maintenance.

What was even more cool about this study, was that it was done on identical twins. 12 pairs of male twins to be exact.

I actually assume this is was a fair representation of their facial expression while trying to overeat for the 84th day.

The reason for this was to examine if there was a genetic similarity in the response to overfeeding in terms of fat gain and where subsequent fat gain occurred.

Basically, if similarities were stronger between twins, we can perhaps provide this as some evidence of genetics playing a role in this.

Study Reviewed: The Response to Long-Term Overfeeding in Identical Twins

Methods

As mentioned above, for 84 out of the 100 days, all subjects were over fed by 1000 calories according to their baseline measurements.

Caloric maintenance was established during a 14 day baseline testing period. Since all subjects were housed during the 120 days of this study, they were served all of their food.

During the basline testing period of 2 weeks, they ate freely in a special dining room. Everything they ate was weighed and measured so the researches could know exactly how much they were eating. Then after knowing baseline intakes and any variations in bodyweight, they had great idea of what their caloric maintenance looked like.

After this period, there was a three day testing phase where they calculated resting metabolic rate, body composition testing and exercise tolerance testing was performed. The same protocol was done for the three days after the overfeeding period as well.

After all of this, the 100 day overfeeding period would begin.

During the 84 days of overfeeding, they would all eat 1000 calories above maintenance with a macronutrient breakdown of 50% carbs, 35% fat and 15% protein.

Essentially everything was monitored. Obviously meals were, since they were served to meet certain intakes, but exercise was as well. All activities were monitored and scheduled.

Bodyweight was taken every day and, skinfold thickness (calipers) was taken every 5 days and waist/hip circumference was taken every 25 days.

Results

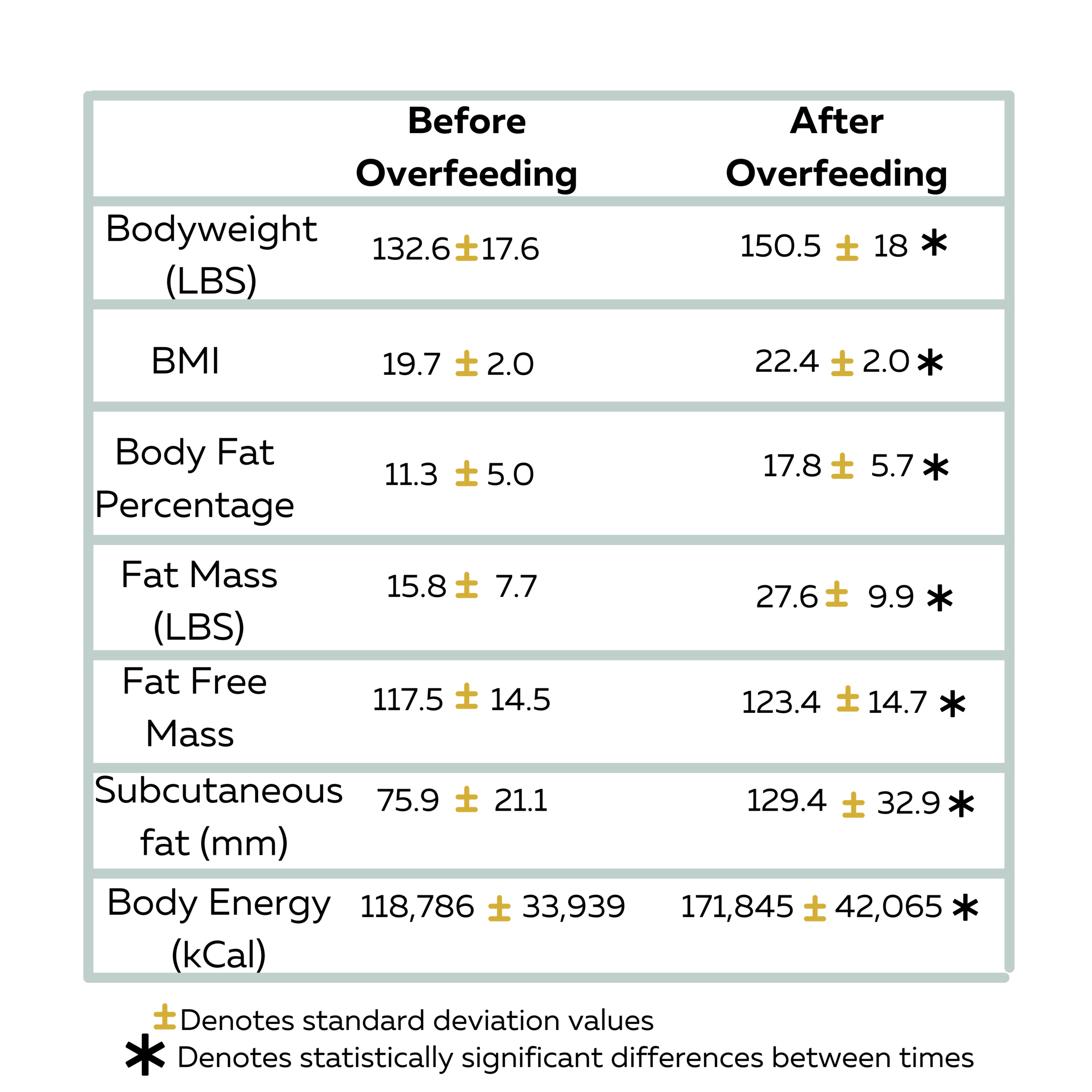

To literally nobody’s surprise, significant weight and body fat was gained by every subject.

The average weight gain during the trial was 17.9 lbs of fat. Interestingly enough, there was a large variance though. With the smallest amount of weight gained being 9.5 lbs and the largest amount being 29.3 lbs. Which is an 19.8 pound difference between the extreme cases.

Which is some evidence into why we really should not be judging people who struggle with their weight. Since as you can see, there may be someone who’s metabolism is just much less forgiving to being over fed than yours.

To expand on this, as the researchers wrote in the paper, the man who gained the most amount of weight essentially stored 100% of excess calories and the man who gained the least, only stored around 40%.

Which had nothing to do with “wanting it more” or simply “having more discipline.” Everything was controlled. Heterogenity is just a reality of life and our individual responses to over eating are not an exception to this.

Below you can see all of the results from pre to post. As all variables increased significantly from before the overfeeding to after.

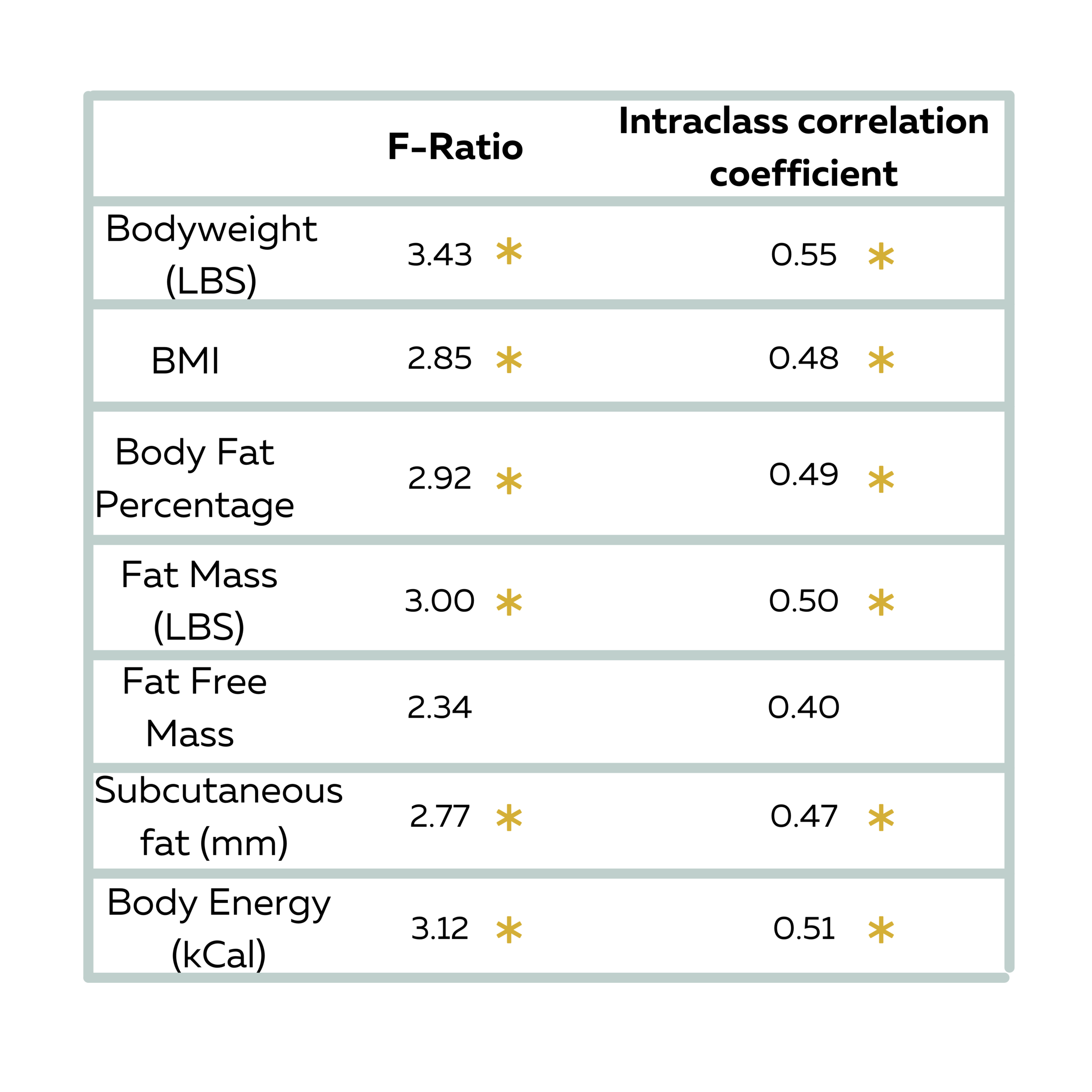

Now what was more interesting, was there was significant findings for similarities between twin pairs. I am no stats expert but I did my best to understand this.

They used an F ratio and an Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)

to see if there was similar responses between groups.

An F ratio close to 1 would be deemed low and would mean the variances between pairs and within pairs would be similar (meaning not much similarity between twins).

While an ICC of 1 would mean a perfect within-pair resemblance in response to overfeeding. Example: both twins gains the exact same amount of weight/fat to a tee. While below 0.40 would be deemed a poor correlation, 0.4–0.5.9 would be fair, 0.6–0.74 would be good and 0.75–1 would be excellent.

Below you can see the general results of similarities within pairs:

You’ll see that all the findings were deemed statistically significant other than fat free mass, which wasn’t showing no similarities, just not ones that crossed the threshold of statistical significance.

With that being said, this paper also broke down regional fat gain (where it was gained) and visceral fat gain which showed even stronger correlations between twins.

With visceral fat mass gained having a 6.1 F-ratio and 0.72 ICC.

Demonstrating there may be some moderately similar responses to overfeeding from genetic factors, but even stronger similarities for where that fat is gained, especially for visceral fat.

Takeaways

I think the biggest takeaway from this paper, is just how varied any individuals response is to overfeeding.

It’s one of the reasons I really loathe fat shaming. Which isn’t to say I never participated in it when I was younger. I surely did.

Our society loves fat shaming people. Whether it be ourselves, family members or really anyone.

With that being said, education (or lack there of) plays a big role on this. It seems we (as a society) still think of fat people as just being gluttons, lazy or just downright slobs.

Which clearly is not always the case. As seen here, some folks may just be burning up to 60% of all excess calories they consume, while some folks store 100%.

To judge in this position doesn’t help anyone, but also isn’t even warranted. Since there is a chance that the person judging may be someone who essentially dispenses the majority of excess calories as opposed to storing them. Which is not even mentioning that stigmatizing weight actually seems to contribute to even more negative outcomes for people struggling with their weight and body image.

Secondly, this highlights how important it is to have an individual approach for anyone who is trying to manage their weight. While also acknowledging that it may be harder for some than it is for others.

I’ve seen this before where two friends are trying to lose weight. Both are killing it from an adherence perspective, but one is seeing much more results.

Yes, sometimes that person may be eating more than they realize, but sometimes they may just have a body that is more resistance to weight loss.

By this, I mean they may conserve energy more effectively when exposed to a calorie deficit than their friend. This is called adaptive thermogenisis and essentially means the body responds to under eating by reducing energy expenditure more than expected to fight further weight loss. Similar to this paper, this is also more individual. While some folks have virtually none of this and some have more of it.

My point is, we all seem to have different responses to overfeeding and underfeeding, which may in fact be impacted by genetics. So our approaches to weight management should be individual and even though it’s hard not to, we should really remind ourselves not to compare our results to others.

Since, one of us may be at a severe advanatage or disadvantage. Which can be demoralizing for the receiver of the short end of the stick.

Your fitness journey and goals are an individual experience. This means you should be comparing you to you. And trying to make improvements based on your goals and your current realities.

Sure, other people can be motivating. I think that’s awesome. But comparing yourself to others may in fact be doing more harm than good. Potentially for both parties.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

*If you find this valuable, please considering sharing with a friend! This helps us tremendously in growing out platform and continuing to help people with our free content.*

References:

1.The Response to Long-Term Overfeeding in Identical Twins

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199005243222101?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

2. The ironic effects of weight stigma

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022103113002047?via%3Dihub

3. Adaptive reduction in thermogenesis and resistance to lose fat in obese men

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19660148/