Could Life Stress Be Impacting Your Strength Gains?

Another instance where less can be more.

By: Dylan Dacosta

6 min read

Heads Up! This was content was first shared on our free newsletter to which you can subscribe to here. No spam. Just high quality fitness content.

You and I, should chill out.

Easier said than done, I know.

But could managing your stress actually lead to better gains in the gym?

Intuitively, you probably think it would. Me too. It’s just that’s not how science works.

Luckily, while there isn’t a tonne of research on this topic it seems, there is some.

Let’s take a peak.

One study from 2014 from Stults-Kolehmainen et al. did show that among 31 college students, the group who was deemed “low stress” via a perceived stress scale had faster recovery markers than those categorized as “high stress” from the same questionnaire.

In terms of recovering maximum isometric force output on the leg press, the low stress group all but recovered by 48 hours. While the high stress group took about 96 hours to get back to basline.

This study was on a small sample size and just measuring short term recovery among stratified stress groups. But it still does show that if you’re dealing with more percieved life stress, it may impact your recovery from exercise. Which I don’t think is too surprising.

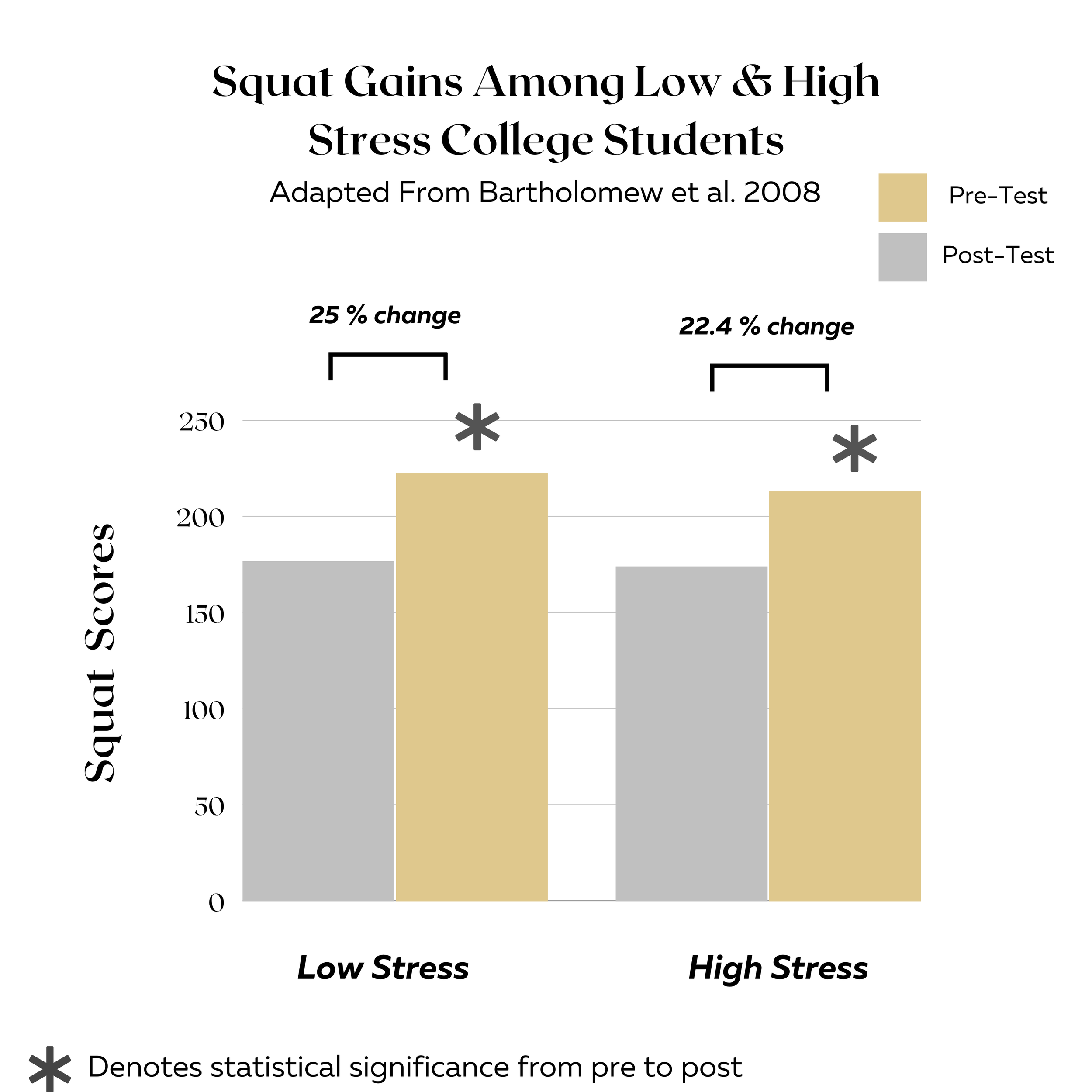

Another study from Bartholomew et al. 2008 investigated long term adaptations to a resistance training program amongst 135 college students. Once again, they were divided into “low stress” and “high stress” groups. The questionnaire used was different here and related more to negative life events and their impact, along with the subject’s perceived social support.

A similar result was observed.

Although both groups did experience significant strength gains on the bench and squat 1RM over the 12 weeks, the low stress groups achieved greater gains in both lifts.

One caveat was that the researchers really weren’t clear on their measures of strength in the paper. It intuitively looks like the scores are 1RMs in kilos, but I find that hard to believe since the groups were mixed sex and not too experienced with training. So the likelihood of them having mean 1RMs on the bench of nearly 150 KG is extremely low.

Regardless, low stress groups did out perform high stress groups in terms of gains. One thing to note is that high stress groups still did make gains. I say this because if you are someone who is more “high stress”, this does not mean you need to master your zen before you can expect any gains in the gym.

Instead, a better interpretation is how the researchers put it in the paper:

Key Takeaways

The limited data we have on this topic seems to point in the direction that higher rates of life stress may impact adaptations to and recovery from training.

I’d say if this holds true, it just confirms most folk’s life experiences in this area.

Another thing is that, I don’t know about you, but my desire to really get after it in the gym starts to trend down when I’m in times of more stress in my life.

You may be the opposite and it might fuel and motivate you more.

I’d just argue that there is going to be a limit to that.

Whether you like it or not, training stress still is added stress.

If you’re someone who says “the gym is my stress reliever”, that could be true on a psychological or sociological level (I know it is for me), but you still need to accept that you are adding physical stress to your body via training. Even though in the long run, that stress tends to be protective and positive.

If your life stress is super high, that added stress from your training might not be as recoverable as it is in other contexts or less stressful periods of your life.

Because that training stress is adding to what you could call your overall stress bucket.

And just like any bucket, if it becomes too full, anything extra just overflows and leads to spillage.

With a literal bucket, that could be as benign as an easily cleanable mess on the floor.

Within the complex human experience, that could mean burnout or breakdowns.

I’m not insinuating that your training is going to lean to a mental breakdown, but it could aid in burnout. I know it has for me.

In those times, I would have been better off reducing the overall intensities/volumes I was training at.

Instead I doubled down because “training was my stress relief.” This led to periods where I loathed the gym because theres nothing quite as shitty as being exhausted and overwhelmed in your life, just to head to the gym and look up at the daunting task of a brutal workout that is not at all appropriate for what minimal energy you have left to give.

Instances like this are hopefully few and far between (I’ve seen this often with new parents that I’ve coached), but when they’re here, remember to factor in whatever additional stress you’re under into your training.

You may need to roll it back a little bit.

You don’t necessarily need to stop training. In fact, I highly suggest against that in most circumstances.

Instead, you could do yourself a big favour by just adjusting your training accordingly.

This might look like doing 2-3 sessions instead of 4.

Doing 45 min workouts instead of an hour.

Or training with less intensity or a farther from failure than you’re used to.

Regardless, holding space and respecting the higher life stress you may be under in terms of setting up you training seems like a great idea to me.

An idea that has some evidence to support it in the limited data we have on the topic.

Lastly, if you’re not under a high stress period, then go get after it!

Life is inherently seasonal. There will always be better and worse times for you to maximize your training. This is just to remind you to hold space for the times you can’t and adjust as you need.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

1. Chronic psychological stress impairs recovery of muscular function and somatic sensations over a 96-hour period

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24343323/

2. Strength gains after resistance training: the effect of stressful, negative life events

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18545186/